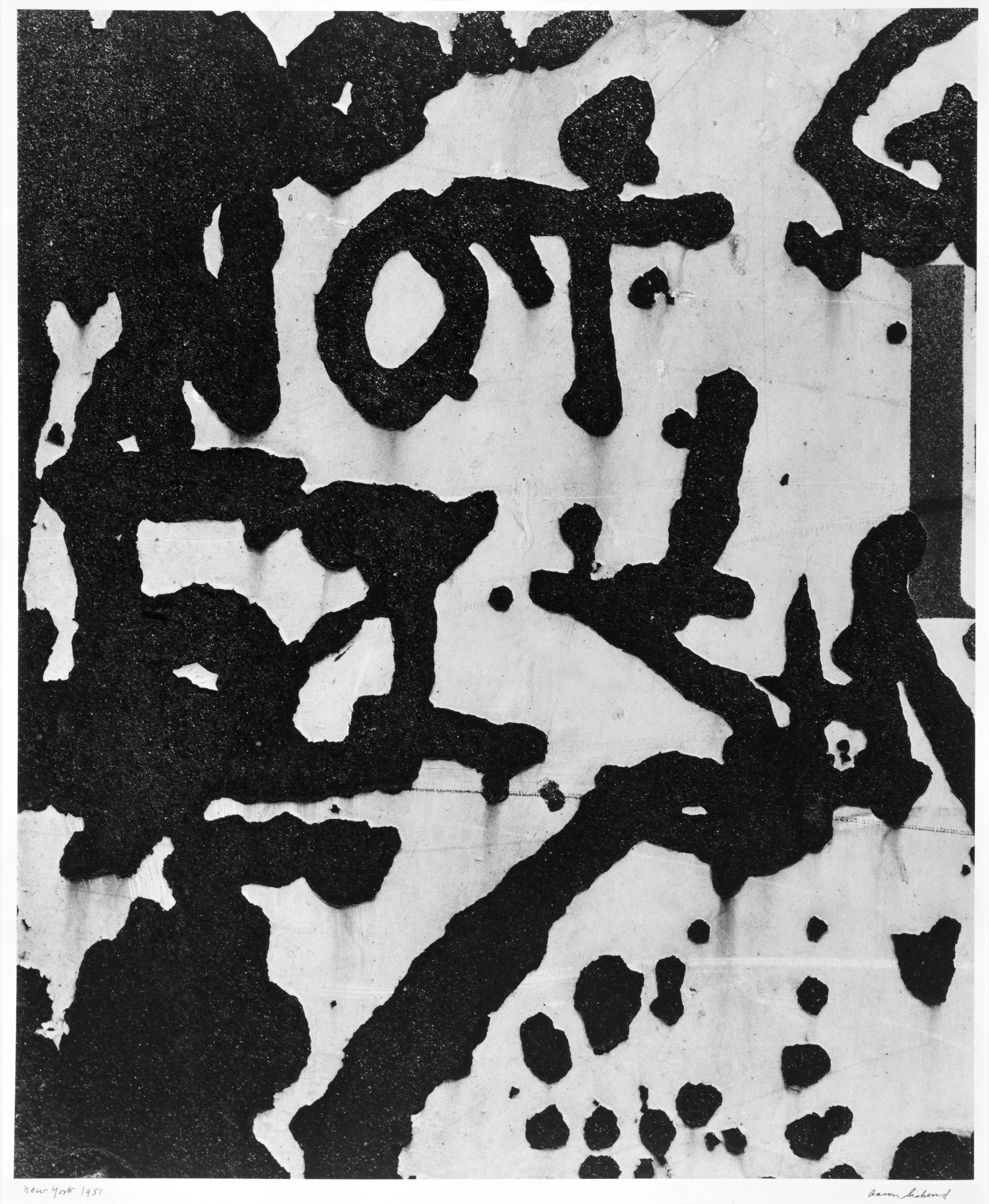

Aaron Siskind

(New York, New York, 1903 - 1991, Providence, Rhode Island)

New York, 1951

1951 (printed mid-late 1960s)

Gelatin silver print

21 1/2 x 17 7/8 in. (54.6 x 45.5 cm)

Collection of the Akron Art Museum

Museum Acquisition Fund

1994.9

More Information

In the 1950s, Siskind was one of the most important American photographers to explore abstraction. This close-up photograph of a rusted metal sign shows that even recognizable images from the real world can appear to be abstractions because of the artist's point of view. Siskind's work recalls the well-known abstract expressionist painters of the period.

Keywords

Black and WhitePhotography

Modern Art

Industrial

Abstraction