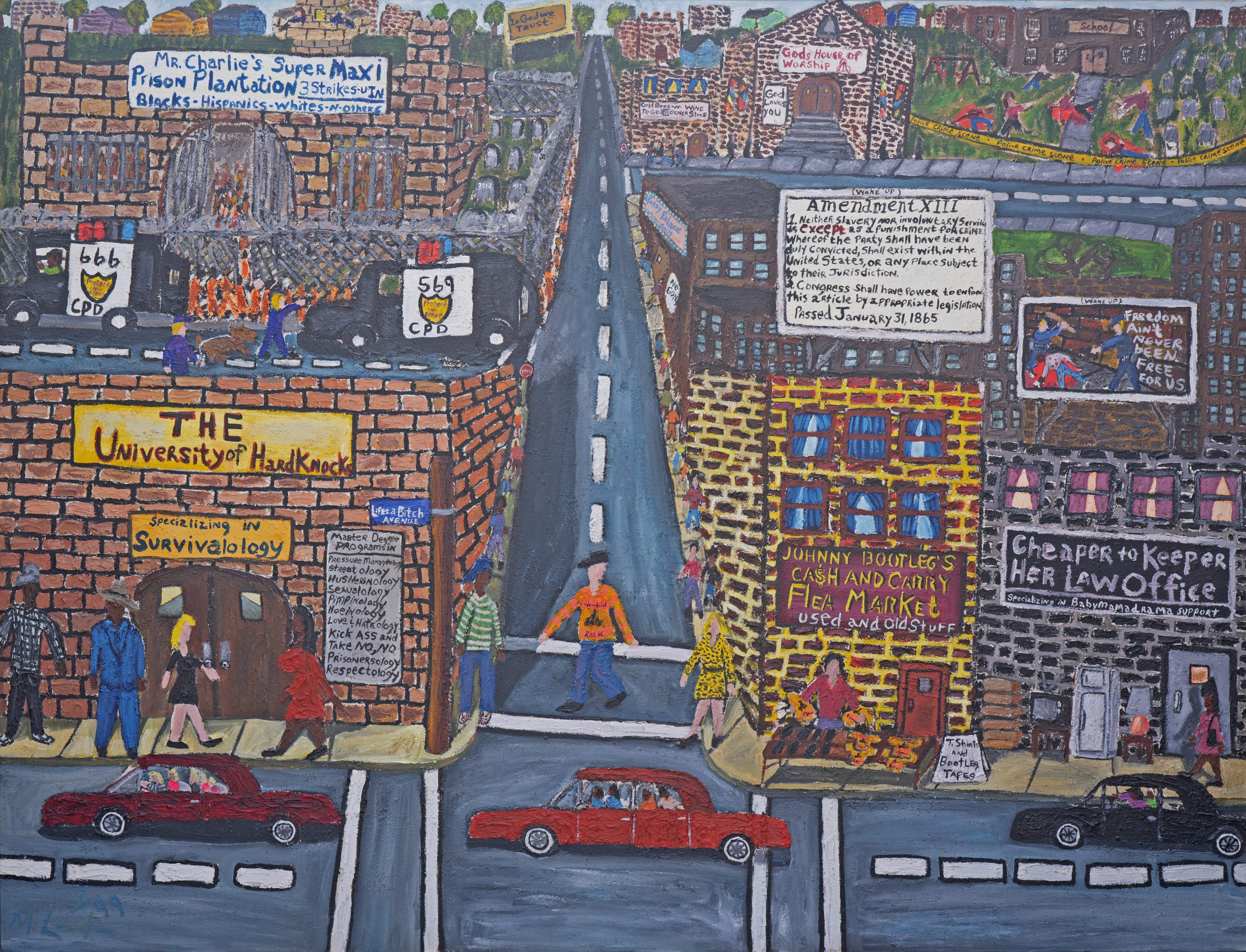

Michelangelo Lovelace

(Cleveland, Ohio, 1960 - 2021, Cleveland, Ohio)

Streetology

1999

Acrylic on textured canvas

53 1/2 x 70 in. (135.9 x 177.8 cm)

Collection of the Akron Art Museum

The Mary S. and Louis S. Myers Endowment Fund for Painting and Sculpture

2024.13.1

More Information

'Streetology' is one of Michelangelo Lovelace’s more pointed and even pessimistic city paintings. Its upper right corner depicts a school shooting—the artist dated the painting to July 1999, and the Columbine High School shooting had taken place in April of that year, so this is a particularly timely inclusion. Lovelace heightened the dire stakes of school shootings by presenting one half of the yard in front of the school building as a playground with a swing set and the other half as a graveyard filled with headstones. The canvas’s the lower left features a “University of Hard Knocks,” located on “Life’s A Bitch Avenue” and specializing in the necessary skills of “Survivalology.” These include everything from love, respect, and pressure management to hate, aggression, and prostitution. Most crucially, across much of the rest of the canvas the artist scattered elements that show his concerns regarding mass incarceration and forced labor. A white billboard reproduces the text of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude—except as punishment for a crime. This exception, which Lovelace highlighted in red, allows prisons to require inmates to perform labor either unpaid or for very low wages. This arrangement continues to be criticized as a system akin to slavery, in part because Black Americans make up a disproportionate part of the country’s incarcerated population. Lovelace makes this point through a maximum-security prison identified by a white sign in the painting’s the upper left, which likens the facility to a slavery-era plantation. Notably, however, the prison includes “Blacks-Hispanics-Whites-n-Others”—all are dubiously welcome, and the prisoners in orange jumpsuits have a range of skin tones. The prison’s motto, “3 Strikes-U-In” plays on baseball’s phrase “three strikes, you’re out” (which is not uncommonly applied in discussions of crime and punishment), and this connects to Lovelace’s own experience of being arrested for drug dealing as a teenager, appearing before a judge, and being told that he had a limited number of chances to change his behavior before he would be sent to prison (Lovelace often referenced this occasion as a turning point, or at least an important and illustrative moment, in his life). While these sharp elements of social commentary are scattered across Lovelace’s composition, they also intermingle with more innocuous elements—a corner store, a church, a strip club, a flea market, a law office specializing in family disputes, and a vendor selling t-shirts and bootleg videotapes. As fully as any other single painting from across the artist’s career, 'Streetology' thus represents Lovelace’s ability to weave his concerns and point of view into the broader fabric of a depicted urban environment. Each billboard, storefront, or block in the grid of a city scene created an opportunity for him to place an idea or a representation of something from his own inner-city community. Streetology is compelling not only for the specific criticisms it offers, but also for its suggestion that all of its many parts are interconnected—gun violence, police violence, incarceration, lack of opportunity, and the more banal pace of everyday life all mix together in a sweeping image of city living. Within the wider timeline of Lovelace’s career, 'Streetology' sits at a notable point of inflection. Stylistically, it represents a midpoint between his first city paintings of the mid 1990s (which feature loose brushwork and a relatively narrow visual vocabulary) and the more practiced examples of his signature style from the mid 2000-aughts onward (which include sharper outlines, more controlled painting, and more extensive use of text). Like many of Lovelace’s earlier works, Streetology is heavily textured, but while its uneven surface gives the image an overall roughness, the canvas is also packed with detail. In subject matter, most of Lovelace’s earlier city paintings are relatively mild, usually portraying moments of everyday life and only engaging in commentary or storytelling through depicted street names or other subtle elements. From 2000 onward he was much more likely to shape paintings with overarching narratives, and he also began painting explicitly political, historical, and allegorical works. Streetology represents the early edge of this tendency and shows its emergence out of the city paintings.