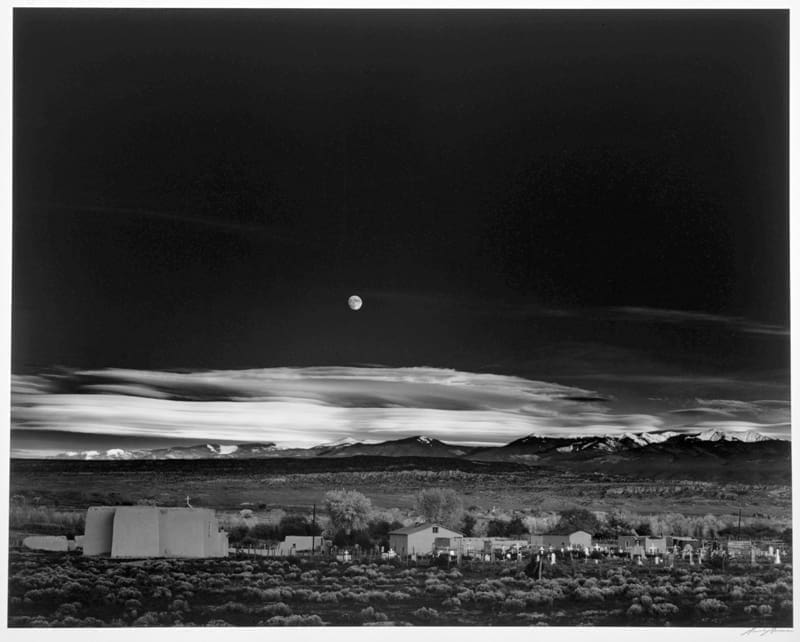

When Ansel Adams saw this particular moonrise, he sprung into action. He grabbed his camera, jumped on top of his car and, when he couldn’t find his handheld light meter, calculated the necessary exposure time in his head. Before he could take a second shot, the twilight was gone.

Adams followed up on his speedy camerawork with painstaking, deliberate printing—trained as a pianist, he compared negatives to sheet music and prints to performances. He darkened the picture’s low tones to make the sky an inky black expanse, and he brightened the highlights to make the crosses in a church cemetery brilliantly white. After thirty years of tinkering, he finally felt that his prints matched what he had seen in New Mexico, and that he had perfected his performance.

What does it feel like to be outside at twilight, when you can see sunlight and moonlight at the same time? Have you ever photographed an outdoor scene, only to find that the light in your picture came out all wrong?

Like many artists and photographers, Adams was often inexact in the dating of his pictures and didn’t know quite when he had taken this one. However, because it became one of his most popular photographs, Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico received special attention and an astronomer friend, Dr. David Elmore, finally came to Adams’ rescue. By studying astronomical data, Elmore determined that Moonrise had been taken between 4:00 and 4:05 P.M. on October 31, 1941. This date, combined with the stillness of Adams’ twilight scene, makes the photograph a powerful image of America on the verge of entering World War II, as the attack on Pearl Harbor came just over a month later.