Over the last few months, we’ve all gotten to know the insides of our homes very well! Interior spaces are particularly interesting to artists since they’re often cooped up in their studios or homes for long stretches of time. Join us for a spin through some of the spaces these artists thought were worthy of attention.

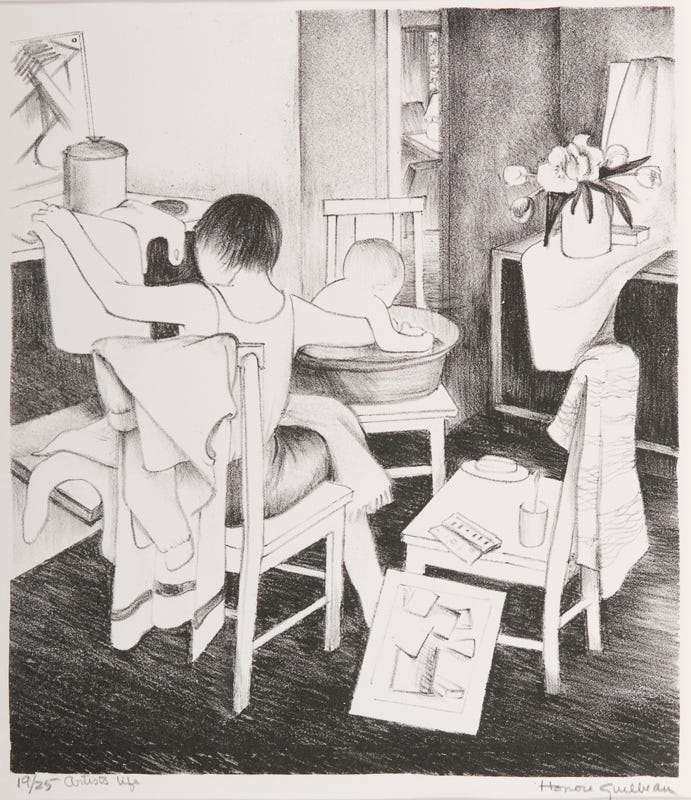

For an artist, there is often little to no separation between home life and working life. In this interior scene by Honoré Guilbeau, we see this coalescence in action. At first glance, it seems Guilbeau’s hands are only full with the work of parenthood as she simultaneously controls her wriggling child and prepares a towel to dry the baby. Bathing scenes like this are common in the history of art. With some closer looking, however, you can see that Guilbeau has added a detail to this work that makes it specific to her life, and wholly relatable to parents during the quarantine era: to her right is a still-life painting in progress and the art supplies and arrangement needed to create it. This is a scene a poignant representation of the balancing act all parents perform.

During the 19th century, artists often depicted women engaged in activities that were becoming of upper-class gentlewomen like sewing, reading, or playing music. For centuries, this domestic sphere of life was considered the domain of women. Men were the rulers of the outside, but at home women were secluded in their own worlds. While this scene depicts a woman near an open window that should provide access to the world outdoors, her back is turned away from the opening and she is cut off from the great-beyond by iron grating and a wall of shrubbery.

This work by Clarence E. Van Duzer seems to defy definition as an interior scene or landscape. The divisions between outside and indoors are almost entirely broken down. Van Duzer presented the viewer with a cluttered tabletop in the sharp foreground with a background of collaged papers, bricks, wooden planks, and a city landscape, but the inside of the space overlaps with the outdoors and vice versa, seeming to suggest that Van Duzer saw the existence of the two spaces as one in the same. Viewing this work is akin to calisthenics for the eyes and brain, as they hop, skip, and jump amidst broken perspectives and slashing lines.

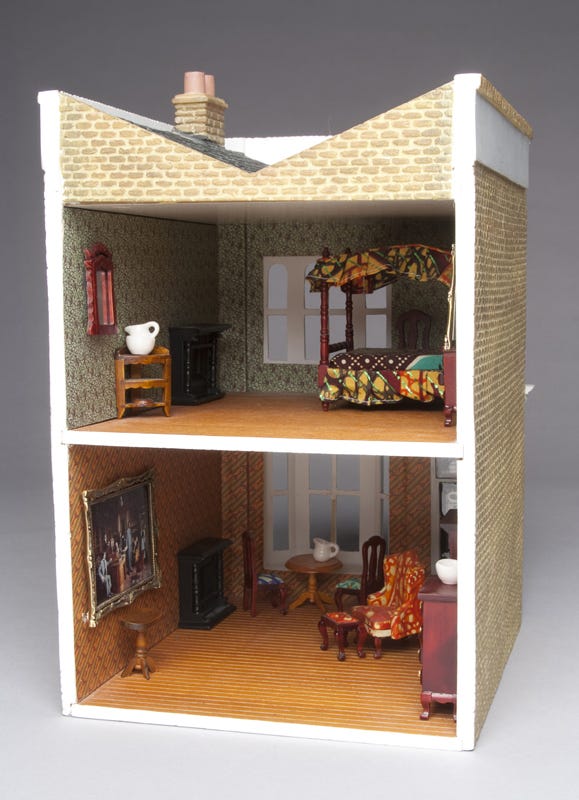

We fill our homes and walls with objects that are reflections of what we care about and who we are. In this work, Yinka Shonibare recreated a miniature version of his Victorian townhouse in the East End of London and filled it with objects that represent his British-Nigerian upbringing. The dollhouse features British architecture and furniture, but Shonibare has included bright bursts of Dutch wax print cloth, which is associated with Nigeria. To fill the walls of the house, Shonibare included a miniature replica of a work by the 18th-century French artist, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, as well as a recreation of one of his own works. This little house is a literal encapsulation of Shonibare’s own identity.

Virtual Tours are made possible with support from the Sandra L. and Dennis B. Haslinger Family Foundation, The Sisler McFawn Foundation, The Welty Family Foundation, Dana Pulk Dickinson, and the Lloyd L. & Louise K. Smith Memorial Foundation.