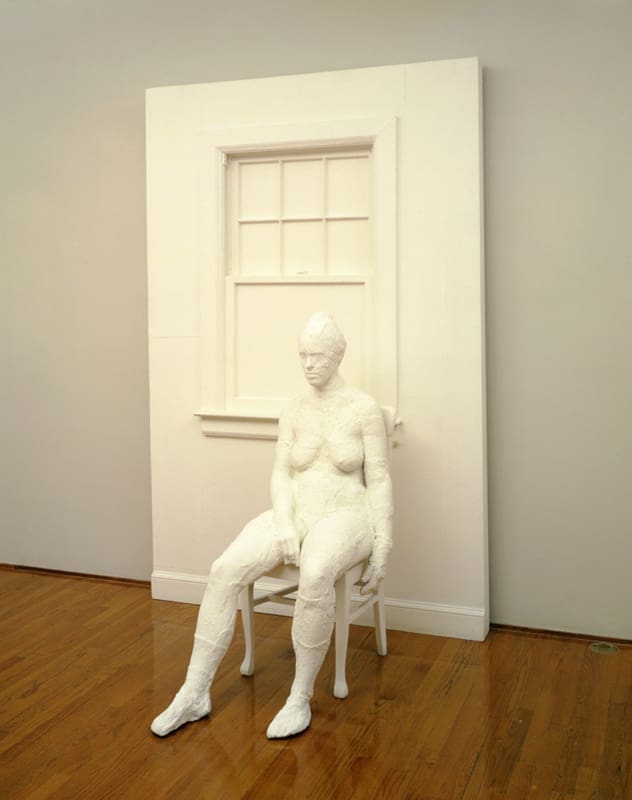

A girl sitting against a wall? Very normal. But what if her world is totally still, totally white, and ends abruptly in the middle of a gallery? Very unusual. In making his sculptures, George Segal thrived on this mix of everyday familiarity and unexpected strangeness.

Segal used living models to create his sculptures. He wrapped them in plaster-soaked bandages and let the materials harden. He then cut the plaster away from the models’ bodies and reassembled the hollow forms. The result: Segal’s white figures seem at once lifelike and eerily motionless. In Girl Sitting Against a Wall II, this stillness may suggest a moment of calm and quiet contemplation. While other artists often depict intense actions or emotions, Segal seems to imply that a restful occasion like this is also worthy of extended consideration.

Segal usually had his family and friends pose for his sculptures. If someone asked you to be covered from head to toe with wet plaster, would you do it? How do you think it would feel to be confronted with a life-sized replica of your own body?

In 1961, Segal was teaching an art class for adults. One of the students was married to an employee at Johnson & Johnson, and they gave Segal a supply of the company’s newly developed plaster bandages to see if he could use them for making art. The artist brought the supplies home and asked his wife to plaster the bandages around him while he sat in a chair. After the soggy materials dried and hardened, his wife kindly cut him out of his mummy-like encasement. The artist then put the pieces of plaster back together and placed the resulting figure amongst a chair, a table, and a window frame. This work, Man Sitting at a Table, proved to be a turning point in Segal’s career and the inspiration for many subsequent sculptures.

Segal’s working process was more laborious and creative than one might expect. “Originally, I thought casting would be fast and direct, like photography,” the artist explained, “but I found that I had to rework every square inch. I add or subtract detail, create a flow or break up an area by working with creases and angles. I’m shaping forms.” Thanks to this process, Segal’s earlier casts produced a lumpy external shape, as seen in Girl Sitting Against a Wall II. The year after this piece was made, Segal developed a new technique, casting a material called hydrostone (which is stronger than plaster) from the interior of the initial plaster shell to give a more refined surface and lifelike rendering.

Segal did not always work entirely in white; sometimes he added colorful found objects to his scenes or painted his plaster in striking tones. The first version of Girl Sitting Against a Wall, made in 1968, is in the collection of the Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart, Germany. Unlike Akron’s all-white piece, this earlier version has a red chair and black window panes, and the figure’s hands are placed differently. As a result, the window seems to look out onto a pitch-black night, while the chair looks like it might be made of wood. Both editions carry Segal’s trademark sense of strangeness, but the earlier rendition’s different colors are perhaps a bit more familiar and easy to understand than the second version’s surreal, all-encompassing whiteness.