By Jeff Katzin, Curatorial Fellow

When I let my mind drift towards broad questions about art, the issues are usually subjective: What makes a work of art beautiful? How can we balance awareness of artistic tradition with a true openness to new ideas? How can artists best communicate truths that are deeply personal? Questions like these are nuanced and exciting, but on occasion it’s a nice change of pace to delve into more objective issues; classic journalistic questions like who, what, when, and where. My last post about Ora Coltman’s Main Street, Cleveland answered a “where” question — Coltman’s scene took place in Cleveland’s Ohio City neighborhood, not on “Main Street,” but rather on Main Avenue. This time around, my research mystery starts with a similarly fundamental question about a work of art: Who?

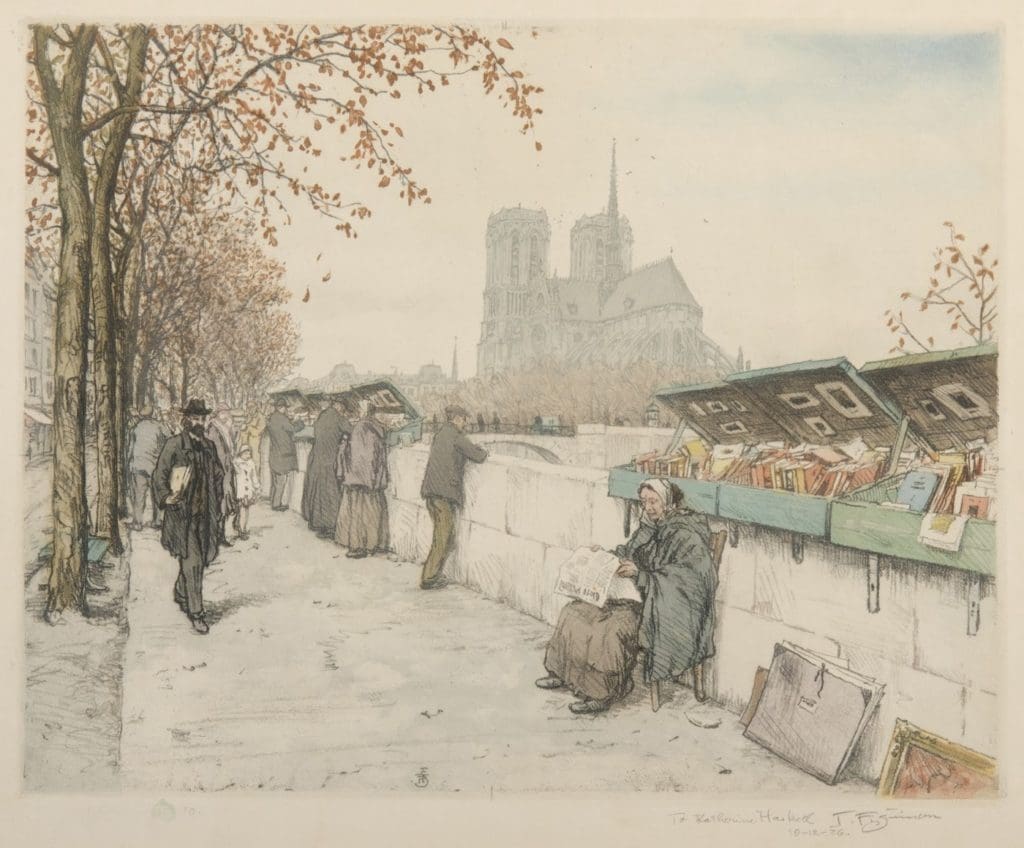

When I was first asked to look into this print titled Bookstalls Along Seine, I figured that there wouldn’t be too many basic questions left to answer. The pictured location is right in the title, and even if that reference to the Seine River, which runs through Paris, wasn’t convincing enough, the famous Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris is clearly visible in the background. As for the artist, he was kind enough to clearly sign and date the print in its lower right margin.

Even working from home and limited to online resources, I figured it would be easy enough to find out a thing or two about T. Frank Simon, his working methods, and perhaps his relationship to the city of Paris. However, when I ran a Google search for his name, I found just one page about artwork (and lots of pages about an immunologist in Kentucky). Even for an obscure artist, that’s a surprising lack of information. The one relevant result, from the Smithsonian American Art Museum, suggested that Simon might be Czechoslovakian, so I thought I’d try searching for “T. Frank Simon Czechoslovakian artist.”

That’s when things really started rolling. I’ll cut to the chase and share this truly amazing website:

It turns out that tfsimon.com pertains not to “T. Frank Simon,” but to a lauded Czech artist named Tavik František Šimon. The website, with a simple visual style but an incredible wealth of information, seems to be a labor of love composed by devoted admirers of his work. Though they certainly deserve it, the authors don’t always take credit, but I did find the names Catharine Bentinck and Eva Buzgova on some pages. Immediately, I became pretty sure that, despite the mixup about his name, Tavik František Šimon was the artist I was looking for. Compare this signature from tfsimon.com to the one from the Akron Art Museum’s print (pictured earlier):

That’s about as good as a match can be! For even further confirmation, the website includes a catalogue raisonné of Šimon’s career — in other words, a comprehensive listing of every known work that he ever made. It’s fantastic to have such an extensive and detailed resource available online. I looked in the graphics in miniature section and, sure enough, I found a matching image, #430. There it’s labeled as Quai de la Tournelle in Autumn, Paris and dated 1925.

This was already great progress, but I was curious about that 1925 date, since it appears that Šimon himself signed the Akron print a year later, “10–12–26.” Assuming for a moment that he actually made this print the previous year, what was Šimon doing in October of 1926, and why would he have added that date?

Once again, tfsimon.com stood ready with a tremendous level of detail. As it happens, the artist had a particularly eventful 1926, as he embarked upon a trip around the globe at the end of August. Before returning to Europe in February of the following year, Šimon saw Cuba, Japan, China, Singapore, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and more, and even made a number of stops in the United States. In fact, on October 12, 1926, the day that he signed the Akron print, he was in Cleveland, Ohio. Here’s his datebook from the time — like I said, the website provides a tremendous level of detail, if you dig far enough into it:

There are two entries for the 12th in particular. The second of these mentions something about “Bailey Art School,” and I was able to solve that one once I made my Google search sufficiently specific — it seems that Henry Turner Bailey would have been dean of the Cleveland School of Art (now the Cleveland Institute of Art) at the time, so Šimon very likely had a meeting with him. That private conversation probably has less to do with the Akron print than the first entry, which reads “Exhibition in the Union Trust Comp.” To figure that one out, I did some more digging on tfsimon.com and found this wonderful piece of archival material:

Coinciding with Šimon’s visit to Cleveland, his friend and supporter William Ganson Rose (a Cleveland-based advertising executive) organized an exhibition of the artist’s works, which was displayed in the downtown lobby of the Union Trust Company. As an aside, Šimon remained friends with Rose for the rest of his life. Not long after the artist passed away, his wife responded to a letter from Rose: “He remembered to his last days the nice journey in 1926 and his kind friends he met on the World trip. On Cleveland and on you Mr. Rose, he had the nicest recollections and spoke often with his family about you.” It’s my guess that Šimon gave the print that eventually made its way into the Akron Art Museum collection to someone at the exhibition that Rose organized, either as a gift or a paid purchase. This idea is supported by what can be found next to the signature and date in the print’s margin:

Now I had come to another “Who?” question — who is Katherine Haskell? I had a sense that I had heard that name before in connection with Ohio history, and so I did a bit of searching and quickly realized that there was a Katharine Haskell who is better known as Katharine Wright Haskell, the sister of the Wright brothers, Wilbur and Orville! In addition to serving as a crucial promoter and supporter of her brothers’ efforts in aviation, Katharine graduated from Oberlin College to the west of Cleveland and eventually split her time between Oberlin (where she was a member of the College’s board of trustees) and Dayton, Ohio (where she taught Latin at Steele High School).

It would be hard to find out exactly why she might have been in Cleveland on October 12, 1926, but the possibility that the museum’s print might be connected to a world-traveling artist and a historically-significant woman is quite enticing. There are a few pieces of contrary evidence, however. First, as you might have noticed above, Katharine Wright Haskell spelled her first name with an A (Katharine), while Šimon inscribed his print with an E (Katherine). But that could be an honest, minor mistake. Second, Katherine Wright did not marry and officially take the name Haskell until November 20, 1926 — too late, but only by a couple weeks! Maybe she asked Šimon to inscribe the print with her upcoming marriage in mind, and maybe he misspelled her first name. Regardless, it’s hardly certain that I have found the correct recipient of the print.

When various COVID-19-related restrictions are lifted, I look forward to finding a copy of Šimon’s diary entries from his world tour — the published collection was somewhat recently translated from Czech into English. If I’m lucky, I’ll be able to take this enticing connection from suspicion to confirmation. For now, I’ll settle for knowing that the Akron Art Museum’s copy of Bookstalls Along Seine is connected to an impressive voyage around the globe — not too shabby.

Coffee with the Collection is made possible with support from the Henry V. and Frances W. Christenson Foundation and the Samuel Reese Willis Foundation.