Take a walk outside without ever leaving your couch!

Hello art lovers — Reggie Lynch, Curator of Community Engagement, here again with another peek at the Akron Art Museum’s permanent collection. This time, in celebration of Earth Day this week, I’m focusing my tour on works that celebrate spring. I know as I take my socially-distanced walks around my neighborhood, it’s been a big relief to see spring flowers poking their heads through the soil. I’m hoping this digital spin through the museum might do the same for you.

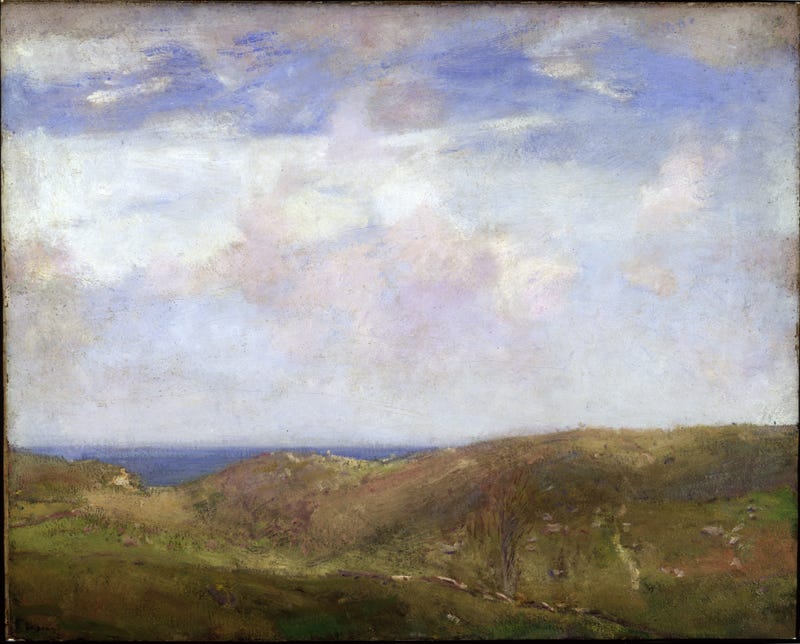

Charles H. Davis, And Southward Dreams the Sea, undated

Maybe it’s my Irish ancestors calling out from the past, but this work has always spoken to me. The exact location of the scene is unknown, and the artist isn’t thought to have traveled to Ireland, but the big blue sky and distant sea below gets me wistful for the blustery spring hills of Ireland. The work’s title, And Southward Dreams the Sea, is likely a reference to the poem “Daisy,” by Francis Thompson, in which the speaker recalls an amorous encounter in a scene much like this one. The title of this work appears in the second stanza of the poem:

The hills look over on the South,

And southward dreams the sea;

And with the sea-breeze hand in hand

Came innocence and she.

Paul Stankard, Brown-Eye Susan bouquet with figures, 1996

The Paul Stankard Glass Collection is displayed on the museum’s second floor in a cozy niche that I often walk by as I go to my office in the morning. Each time I do, I’m always surprised to find new details in each little scene. These glass sculptures play on the traditional glass paperweight form, which reached its height of popularity in France during the 19th century. The small figures, flowers, and insects that fill Stankard’s works are entirely made of glass, using a process called flameworking. His minuscule worlds explore cycles of birth, decay, and the unseen forces that usher in these changes. As I’ve walked around my neighborhood these last few weeks, slowly taking in the miniate of spring, these vignettes have popped into my mind.

John Henry Twatchman, The Winding Brook, 1887–1900

Childe Hassam, Bedford Hills, 1908

In looking through the museum’s archives, I found myself drawn to this pairing of John Henry Twachtman’s The Winding Brook with Childe Hassam’s Bedford Hills from a past exhibit Landscapes from the Age of Impressionism (2011). Their place next to one another perfectly encapsulates nature’s diametric pinnacles of color, with Twatchman capturing nature’s autumnal reposing breath, and Hassam showing nature’s first signs of spring. Both artists were early champions of American Impressionism, which was an art movement that prized brightly colored representations of nature. Hassam often went so far as to directly apply paint from the tube to the canvas, as opposed to first mixing pigments to lower their contrast. Often when giving a tour, I’ll stop the group in front of one of these works and ask them to quietly place themselves in the scene. What smells are wafting along on the breeze? What rhythms are playing out in the meandering stream? Can you feel the sun warming your cheeks?

Tiffany Studios, Hanging Head Dragonfly Lamp, after 1902

Not all landscapes are paintings. Some of the best depictions of nature from the 20th century were created by Louis C. Tiffany and his Tiffany Studios. Tiffany was an advocate for the Art Nouveau and Aesthetic movements, which focused on showcasing beauty and craftsmanship above all else. Nature and sinuous lines were staple features of both these movements. In this lamp, dragonflies hover at the edge of a dappled green shade, as if poised on the banks of a rippling spring pond. The shade’s abstract pattern also mimics the delicately webbed texture of a dragonfly’s wing. Furthering this natural theme, the base of the lamp was designed to look like a cluster of pond reeds that extend up from a water lily. The overall effect is one of quiet contemplation. You can almost hear the trees rustle as a breeze lifts these dragonflies through the air.

Thanks for joining in on this mini-nature walk through the collection. If you’re feeling curious about the rest of the museum’s landscape collection, you can always check out more of those works here.

Virtual Tours are made possible with support from the Sandra L. and Dennis B. Haslinger Family Foundation, The Sisler McFawn Foundation, The Welty Family Foundation, Dana Pulk Dickinson, and the Lloyd L. & Louise K. Smith Memorial Foundation.