Tag: museum

Ralph Albert Blakelock

In this moody night scene, or “nocturne,” Ralph Albert Blakelock captured the solitude and stillness of night, rendered through hazy shades of green, blue, and black. Blakelock was known for his nocturnes, which his biographer characterized as representing “that strange, wonderful moment when night is about to assume full sway, when the light in the western sky lingers lovingly, glowingly, for a space, and the trees trace themselves in giant patterns of lace against the light.” These scenes illustrate Blakelock’s subjective responses to nature and

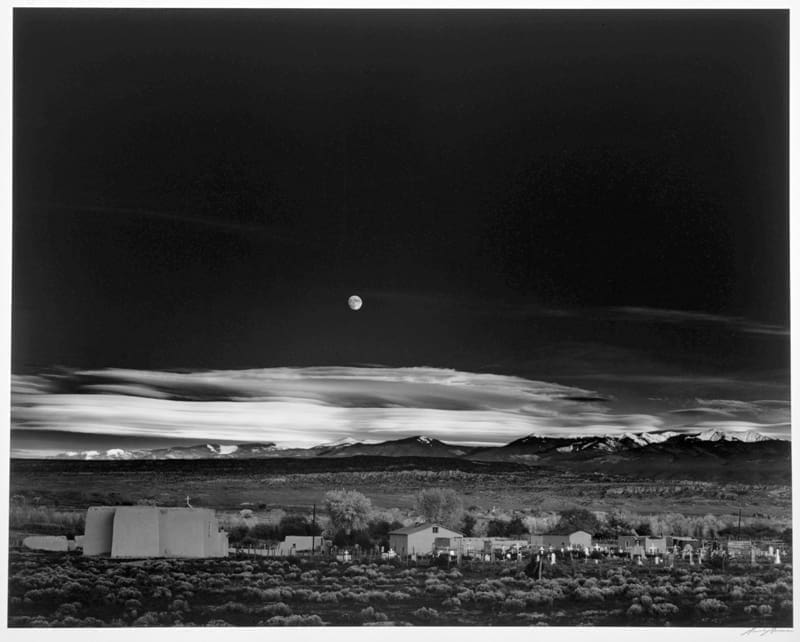

Ansel Adams

When Ansel Adams saw this particular moonrise, he sprung into action. He grabbed his camera, jumped on top of his car and, when he couldn’t find his handheld light meter, calculated the necessary exposure time in his head. Before he could take a second shot, the twilight was gone. Adams followed up on his speedy camerawork with painstaking, deliberate printing—trained as a pianist, he compared negatives to sheet music and prints to performances. He darkened the picture’s low tones to make the sky an inky