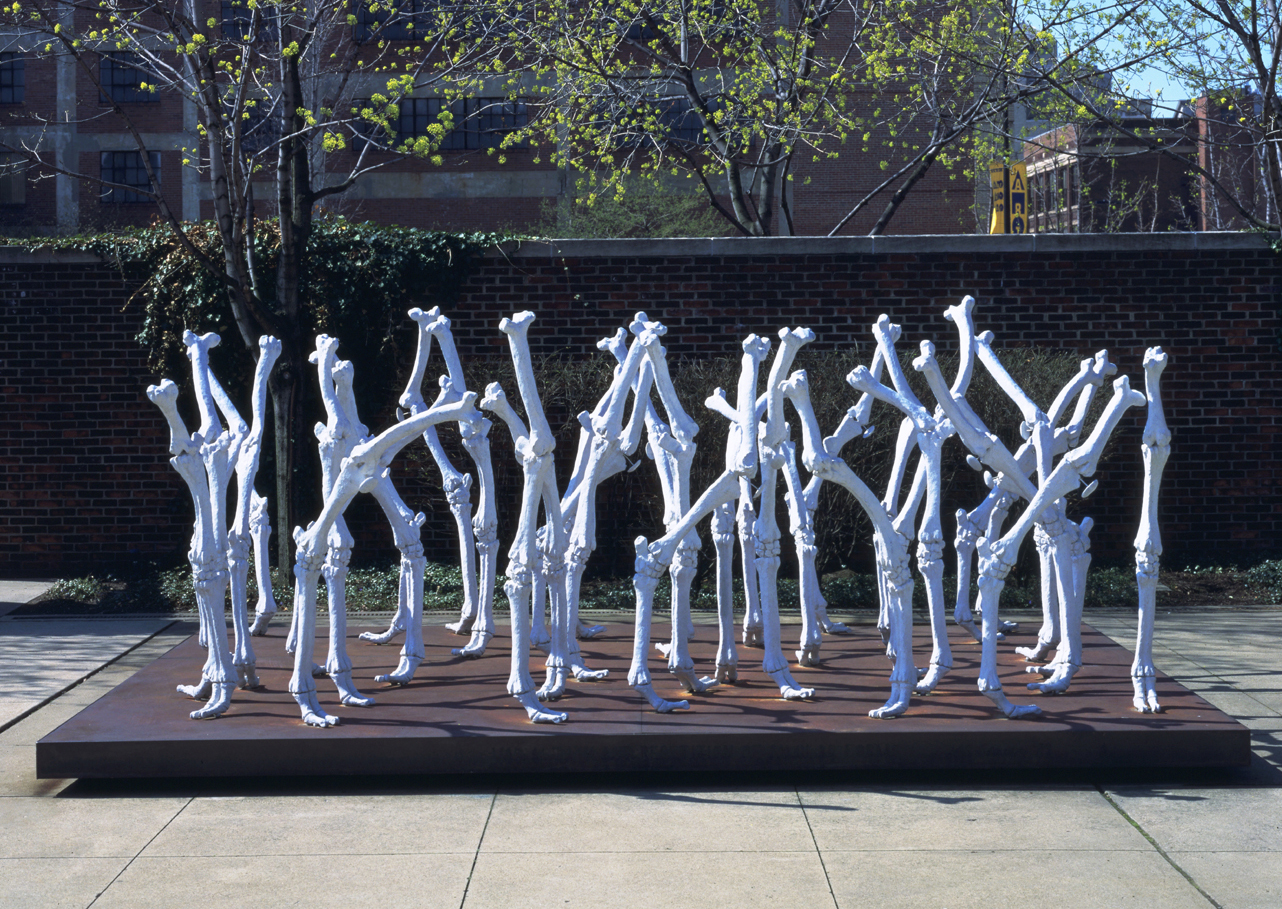

Nancy Graves

(Pittsfield, Massachusetts, 1939 - 1995, New York, New York)

Variability and Repetition of Similar Forms II

1979

Bronze and Cor-ten steel

72 x 192 x 144 in. (182.9 x 487.7 x 365.8 cm)

Collection of the Akron Art Museum

Purchased with funds from the Mary S. and Louis S. Myers Foundation, the Firestone Foundation, National Endowment for the Arts, and the Museum Acquisition Fund

1981.15

More Information

Abroad in Florence, Graves experimented with sculpture while investigating taxidermy and antique anatomical models. Her first sculptures were of camels. She eventually created twenty-five large, realistic camels constructed over wood and steel armatures from burlap, wax, animal skin, and other materials; most of these were eventually destroyed. Relocating to New York in 1966, Graves continued to pursue her interests in anatomy, anthropology, and archaeology. She also worked in film, drawing, painting, and printmaking. In 1976, a German museum asked Graves to make a permanent version of an earlier sculpture in plaster, which initiated twenty years of experimental processes in casting and coloring bronze. She became a key figure in the revival of bronze as a favored medium for sculpture at a time when most sculptors favored industrial methods and architectural constructions. Whereas in the earlier life-size replicas, Graves examined a camel's external appearance, in Variability and Repetition of Similar Forms II she explored the animal's inner structure. The origin of this work can be traced to Morocco and Los Angeles in 1970, when Graves made an eight-minute film showing camels in rhythmic tableaux that seemed "to have been posed and choreographed by sheer will power on the part of the director." Around the same time Graves pursued a longtime interest in fossils by making drawings of an articulated Pleistocene age camel skeleton at the Museum of Natural History in Los Angeles. These drawings, along with photographs, led her to make thirty-six separate legs formed from wax over steel armatures and colored with marble dust and acrylic paint. Their arrangement into a dancing chorus of legs echoed the ideas of movement and patterning explored in the films. The Akron Art Museum's piece is not identical to the thirty-six plaster legs of 1970; it is a unique bronze made nine years later. Graves wanted to execute this second version in a material that could be shown outdoors. To transform the piece into bronze she made six wax casts, each subtly different from the others. The resulting bronze legs were bolted onto a Cor-ten steel base and covered with white wax to enhance the bonelike quality. Though Variability and Repetition does not move, the legs, abetted by the elevated arc of the foot and ankle bones, display a delicate sense of balance. Graves explained: "One of the ideas in that piece, as everyone walks around it, is [that] the illusion of motion is introduced so that the legs simply seem to move." The cinematic effect reflects the artist's involvement in film and her interest in the pioneering nineteenth-century photographs of Eadweard Muybridge depicting animal and human movement in stop-action sequences. To Graves the animal world appeared to represent a superior and more ancient form of life than that of the human body. Her odd subject matter, however, is not the only reason her work is startling. The art historian Linda Nochlin explains that Graves challenges our expectation that zoology and art are separate. "Boundaries between the activities of science—observation-research, systematic investigation, archeological reconstruction—and those of art—invention, creation, construction, imaginative play—are purposely left undefined and open." Graves's scientific curiosity is imbued not only with imagination but with an affecting empathy that eschews morbidity in favor of animation and theatricality.

Keywords

MetaphorSculpture

Bronze

American

Skeleton

Camel

Bones

Leg

Death