Amanda King

(Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 1989 - )

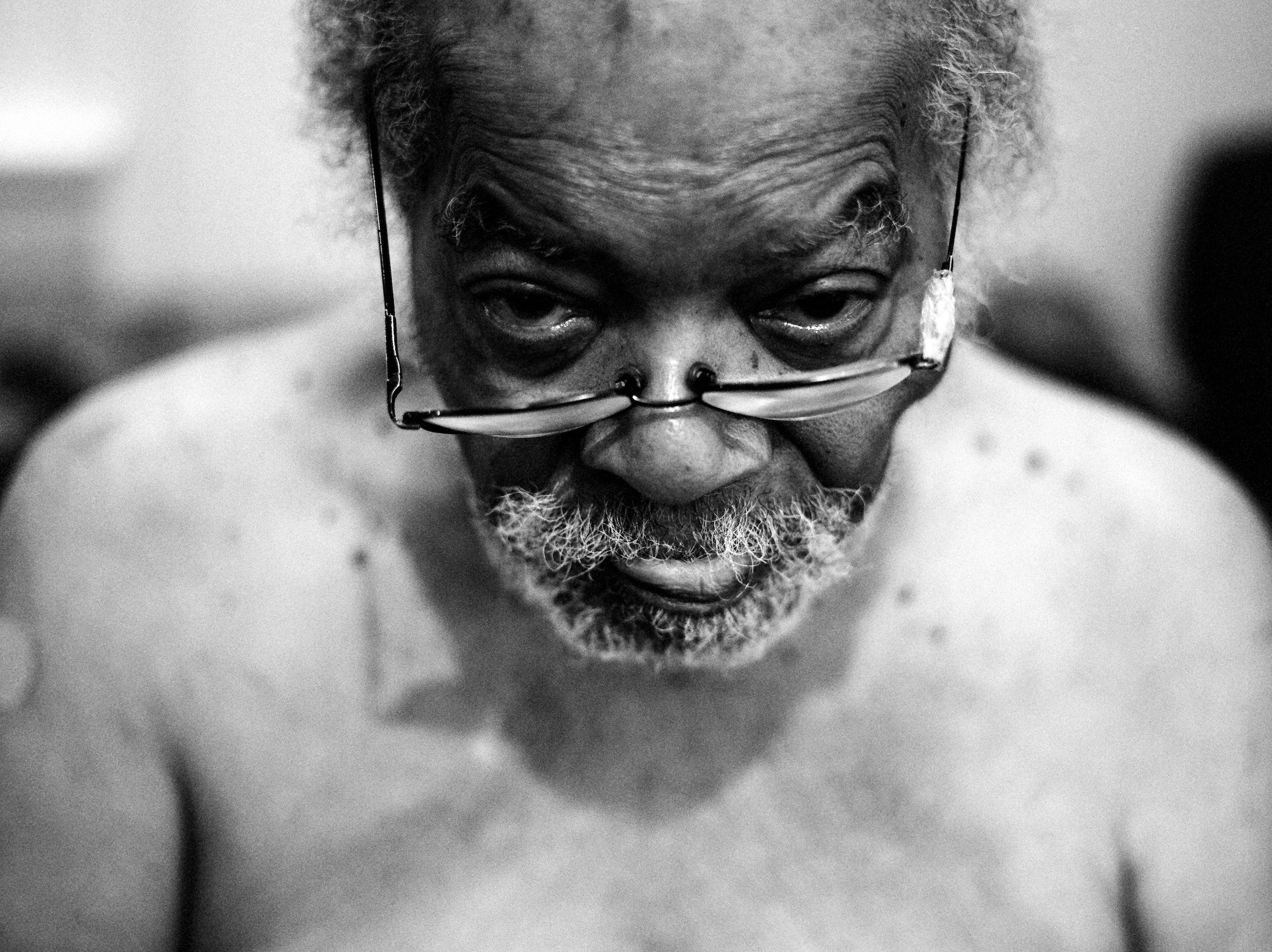

Grandad's Bedroom, January 20, 2021

2023

Black and white photograph on jacquard duck cotton

40.5 x 46 in. (102.9 x 116.8 cm)

Collection of the Akron Art Museum

Courtesy of the artist and Foothill Galleries of the PhotoSuccession, Cleveland, OH

2024.3.1

© Amanda King

More Information

These three photographs are drawn from Amanda D. King’s broader body of works titled “Locusts.” When selections from the series were displayed in a solo exhibition in the Akron Art Museum’s Bidwell Gallery in 2023, the artist provided this statement, which served as the show’s introduction: On February 10, 2021, Amanda D. King’s grandfather, William C. King Sr., died from COVID-19. Bearing the gravity of the pandemic while still living within it, King documented her grandfather’s illness and her family’s experience in the aftermath of his death. In creating and presenting this work, the artist leans on Christian spiritual mythmaking to help her face the devastating impacts of the global plague. The title Locusts is drawn from the biblical scripture, “I will restore to you the years that the swarming locust has eaten...” (Joel 2:25). This exhibition explores the role of memory in grief, history, and spirituality through photographs depicting intimate, visceral, and challenging moments. Locusts offers an opportunity to understand and grapple with lingering sorrow, layered memories of deceased loved ones, social crisis, and grace. At the time of her grandfather’s passing, King’s parents also had COVID, and so she found herself taking care of all three family members. As her grandfather’s condition worsened, the hospital extended an invitation for one relative to say goodbye, amid the conditions of the pandemic that precluded a larger group of visitors. Amanda was the only one who was available to go, and so she went simply as a family member, but also brought her camera, as she views photography as her means and language to convey emotions and understand the world. Much of her work has dealt with the suffering and death of Black people, and as a result King expected that casual phone photographs would enter the real of the grotesque, so she brought a film camera to more carefully work with light, shadow, and composition, and to capture elements of her grandfather’s passing obliquely, extending a manner of protection. A story that the artist shared in a 2020 interview helps to expand upon this point: When I was twelve, I attended an exhibition of lynching photos at the Andy Warhol Museum. Witnessing the racial terror within those photos, my parents’ visceral response (a combination of agony and deference) to the work as they moved through the gallery and the non-Black patrons gazing at the brutalized Black body in silence was a very strange and terrifying experience. It felt morally wrong to passively look at the pain of others when they did not consent to our gaze and have the license to walk away without action. I believed we owe them more for their suffering. I did not know how to articulate this feeling. This was in 2001. Since then Black death has been commodified and normalized in the art world, media, and popular culture to the point where we are all desensitized to it. This has created a collective apathy that I believe we must actively resist.3 With these experiences and histories in mind, the artist carefully calibrated how much is revealed in the photographs of her grandfather, both for their circulation within her family and for their public display. King’s relationship with her grandfather had also long been mediated through photography, even in wholly mundane moments, and so its involvement here seemed natural. The resulting images are as close to a family archive as they are to social documentary, and they work effectively in both contexts. While their titles are straightforward markers of time and location, the images themselves are more poetic. This entire body of work is informed by King’s sense of death not as a final stage of life, but rather as a transition, from life to afterlife. This view is rooted in her grandfather’s Black Christian faith and his full belief in life beyond death. King hopes that this perspective’s articulation in her work would bring comfort to him in his transition, and to those who have been or who remain fearful during the COVID-19 pandemic. The artist is quick to note that this work was created during the height of the pandemic when trends of infection and death were not yet improving, and different variants of the disease were steadily emerging. Amid broad despair and discouragement, as well as social upheaval surrounding race, King looked to scripture and myth to find solace and optimism. The presentation of some of these pictures as tapestries emerged from King’s sensitivity to form and texture within photography. Through her images, she made note of bed sheets, hospital curtains, and the plush fabric of a casket as significant parts of her grandfather’s journey. She also noted the draping of cloth over his body, and its dressing with spices, oils, and fabric in preparation for his funeral and burial. The tapestries serve to bring these forms of shrouding, of protecting the body, into a gallery presentation. By suggesting care, this presentation also helps to strike the balance between social documentary and familial intimacy that the artist sought throughout her work on the series. Grandad’s Bedroom, January 20, 2021 King’s personal favorite in the “Locusts” body of work, this is the last image of her grandfather living fully, experiencing some discomfort but still in his home. In his eyes, she sees an intimate connection, as if he’s asking “Are you taking my picture right now?”—a very natural moment between a grandfather and a granddaughter nicknamed “Mandy Warhol” for the constant presence of a camera in her hand. This image also serves as a start for the series with her grandfather sitting up in bed, whereas he would later lie down in the hospital or in his casket. The tape on his glasses helped to keep them in place when he had become too fatigued to mind them himself. The bandage applied following the COVID-19 vaccination shot that failed to save his life is faintly visible on his right arm, at the left edge of the image.