Media

Museum Meditation: Frankenthaler

Helen Frankenthaler’s stain painting Wisdom has the feel of a watercolor. Frankenthaler actually employed acrylic to stain the canvas. The uneven tones of color are subtle, offering the eye a surprising topography.

Wisdom

Helen Frankenthaler

(New York, New York, 1928–2011, Darien, Connecticut)

Acrylic on canvas

94 in. x 112 in. (238.76 cm x 284.48 cm)

Gift of the Mary S. and Louis S. Myers Family Collection in honor of Mrs. Galen Roush

1978.39

Elias Sime: Tightrope

Complex tableaus made with nontraditional materials

Elias Sime: Tightrope, the first major traveling survey dedicated to the Ethiopian artist’s work, is on display at the Akron Art Museum through May 24. Sime’s March 29 artist talk has been canceled as part of public health efforts, but you can take a close look at his large-scale tableaus made of reclaimed electronic components and learn more about the artist’s work in his own words through this virtual tour on all AAM’s social platforms. Enjoy the #MuseumatHome.

Elias Sime: Tightrope is organized by the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, Clinton, New York.

Its presentation in Akron is made possible through the generous support of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation; Ohio Arts Council; The Tom and Marilyn Merryweather Fund; the Kenneth L. Calhoun Charitable Trust, KeyBank, Trustee; Katie and Mark Smucker; and Mr. and Mrs. Joseph S. Kanfer.

Each material I collect has its own story. It has its own language. Every story has a beginning. I think about the first person who thought or dreamed of it and all the people who transformed that dream into a material. I also think about the various people who used and reused the material before it landed in my hands. I never worry about how old or new the material is. My art is not about recycling or repurposing material but about expressing my ideas. For instance, when I first saw a motherboard, it reminded me of a city, of landscapes, as well as of the people in the factory who assembled it.

— Elias Sime

I have done a lot of work using clothes buttons. When you wake up in the morning, you open your button or button-up, and you do that with care. It is an expression of love. It puts you in contact with your body… [Buttons] tell the stories of the persons who used them; the human traces they hold are expressions of love. — Elias Sime

It took me a great deal of time to collect the keyboards. Keyboards have evolved very quickly — the ones today use a completely different technology from a couple of decades ago, but their colors are monochromatic, which gives an impression of silence. Sometimes, thoughts are expressed through noise, and other times, through silence. The keyboard is not loud, but it is full of symbols. — Elias Sime

The only thing I think about when I pick the cellular phone motherboard, for instance, is the excitement of the person who owned it the first time they got it. The hope they felt about the future, the eagerness to use it. That, for me, is what love is all about. To realize that we are all connected and that human contact, that touch, is created in every object we take for granted. — Elias Sime

The materials I select, by the time they get into my hands, they’ve been touched by so many people, and now they’re in my hands. Even though it may not be visible, when you’re working on your personal computer, you leave a part of you on that. Then, when it breaks, there is somebody else who goes inside it and touches it: there’s that fingerprint, that connection that you can even have with the machine. Technology is very tactile. It’s connected to us. That doesn’t mean it’s going to be beneficial for us, 100 percent. It actually made us lose a lot of things, too. It gave us speed. But we have also lost that calmness, tranquility, and quiet. — Elias Sime

Read MoreRelief Printing

Relief prints are easy and flexible. The basic premise is that anything raised from the surface will transfer ink onto the paper. A stamp is essentially a relief print. Linocut prints and woodblock prints are two commonly used forms of relief printmaking.

At home, you can create a type of relief print using cardboard and foam stickers. If you don’t have foam stickers, you can use old styrofoam and hot glue. If you don’t have printer’s ink, you can brush acrylic paint onto the block. Any paper can be used for the print, but thicker paper often works better.

This type of printmaking is most successful when you work with big, bold shapes, rather than finely crafted, minuscule decorative elements.

The prints can be used for postcards or just decoration.

Objects to Be Destroyed

The artists in Objects to be Destroyed use unusual materials to create their works of art. They incorporate natural matter or manufactured products directly into their sculptures, assemblages, photographs or video.

Artists, curators and scholars use the phrase “found objects” to refer to non-art materials that are included in artwork. These items are found — or sometimes purchased — by artists, who value them for the way they look or the ideas they inspire. Found objects may simply be placed on a pedestal or wall and treated as works of art, or they can be modified by artists before display. Artists often use found objects in assemblages, which are artworks created by organizing multiple objects into a single composition.

Objects to be Destroyed is full of everyday items, including a clock, an umbrella, a lightbulb and two potholders. Here are five other things to spot in the exhibition:

Food Dye

Tony Feher filled forty-nine glass bottles with water tinted by different proportions of blue food dye for his untitled 2013 work. The color progresses from dark to light and back to dark again six times. Feher compared this progression to the nuanced hues in the sky and ocean. The pulsating blue, he observed, resembles a rolling wave — the form energy takes as it travels through air or water.

Books

Nina Katchadourian was an artist-in-residence at the University of Akron in 2001 when she snuck thirteen stacks of books out of the Akron Art Museum library and placed them behind the reception desk. She arranged the books so the words on their spines formed short poems, stories or aphorisms, many of a humorous nature. These groupings are represented in Objects to be Destroyed by photographs that the artist made as part of a series she titled Akron Stacks.

Rocks

While on a walk in the West Texas desert in 2015, John Newman stumbled upon a small pile of stones. The way the rocks were stacked reminded him of a sitting figure, and their rich hues — including pink, slate gray and tan — caught his eye. Newman scooped up the stones and brought them back to his studio, where he created Tracking and Stacking in Self-Reflection (in Marfa). Inspired by the idea of reliquaries (containers housing holy objects), he crafted a pillow-like form to support the rocks and a dome-like structure with a mirrored interior to reflect them — and closely peering viewers.

Disco Music

For Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman, a video made in 1978 and 1979, Dara Birnbaum paired footage from the 1970s television series Wonder Woman with the 1978 song Wonder Woman in Discoland. Following Birnbaum’s edited scenes from the TV program, written lyrics to the disco song scroll up the screen as the music plays in the background. These lyrics, including phrases like “Shake thy wonder maker,” highlight the sexualized nature of the show’s presentation of a superhero associated with female empowerment.

Pipe Cleaners

Lucky DeBellevue twists colorful pipe cleaners together into loops, connecting them to build pyramid-shaped structures he displays on top of cafeteria trays. When he first started using pipe cleaners, DeBellevue said he “went with something that was very basic and memorable to me as a child, something I assume others had used in their arts and crafts classes as children or had some other kind of experience with.”

by: Theresa Bembnister, Curator of Exhibitions

Objects to be Destroyed is organized by the Akron Art Museum and supported by funding from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and the Ohio Arts Council.

Read MoreCrossword June 14

Nothing better than enjoying a puzzle on a summer day. Join The Franklin Institute, Canadian War Museum,Air Force Space & Missile Museum, the Contemporary Jewish Museum, The Royal Saskatchewan Museum, the Ancient House Museum of Thetford Life, the Lynn Museum, Stories of Lynn, the Allentown Art Museum, and the Akron Art Museum.

To play online. To download a pdf.

Across

4

Colds that last a long time

5

Museums tend to put things on a ___.

7

This future member of the Group of Seven was wounded at the Battle of Mount Sorrel in June 1916 and later served as an official war artist from 1917 to 1919. The Canadian War Museum has more.

8

The ocean around Cape Canaveral became known as “_____-infested waters” during the 1950s due to guidance system issues of this Air Force pilotless bomb tested there. Learn more at the Air Force Space & Missile Museum.

9

Shimmel Zohar, a mythical 19th-century Jewish immigrant, founded Zohar Studios, whose work in THIS MEDIUM created an idiosyncratic vision of Victorian life in the United States. Learn more at the Contemporary Jewish Museum.

10

Which Walter taught at King Edward Seventh School and died in a motorcycle accident on Saturday Market Place in Kings Lynn? Learn more at the Lynn Museum.

13

Common in Historic Houses

15

Natural History collection object

16

Gallery ___

18

Eponymous pictograph that represents Canada’s only known written record of Treaty promises from the viewpoint of the Indigenous people. Learn more at Royal Saskatchewan Museum.

Down

1

Middle school homework or natural history museum regular

2

Not Big, but important, is what you’d call Allentown Art Museum’s Frank Lloyd Wright Library from this family.

3

Often seen atop 1 across

5

Starry Nights during the day

6

What is the name given to a medieval ground (street-level) cellar or storage room, often brick-lined and vaulted, one of which is Stories of Lynn?

11

Line Marker

12

The hippocampus, which plays an important role in long-term memory, is shaped like a ___. Learn more at the Franklin Institute.

14

This painter’s last name means “beautiful.” The Georgia Museum of Art can give you a hint.

17

What flower is on the unusually prominent high hooded canopy over the doorway at Ancient House? Learn more at Ancient House Museum of Thetford Life

18

Group of talking heads or non-art wall hanging

Read MoreWhat’s Your Social Isolation Mood?

Social isolation has brought out so many emotions, often at the same time. Our photography collection might help you track your emotions.

- Dieter Appelt began his career as an opera singer, but then transitioned into photography. He traveled extensively specializing in long exposure photographs and images of slow moments.

- Tiny was a prostitute living in Seattle that photographer Mary Ellen Mark captured when on assignment for LIFE Magazine. This image typifies Mark’s unsparing, empathetic style.

- Deborah Luster has photographed people in the deep south for much of her career. These portraits, like this one, seem to show an inner sense of the sitter.

- American artist Judith Golden often plays with photography, like in this image where a photograph is held by the sitter, only to be photographed for the final composition.

- Ralph Eugene Meatyard is best known for his photographs that examine the bizarre and mysterious realms that exist within our everyday world.

- Weegee, a freelance press photographer whose lurid photos of crime and accident scenes frequently appeared in tabloid newspapers, often played manipulating compositions like in this photograph.

- Prolific photographer Walker Evans’ scenes of everyday life often show people in candid moments.

- Margaret Bourke-White had a long career as a documentary photographer, gaining some of her early successes in Cleveland.

- Vernon Cheek studied with Harry Callahan before going on to founded the photography department at Perdue.

Cooking with the Collection: Claes Oldenburg

This regular series uses the Akron Art Museum’s collection as a source for inspiration for meals to cook at home. Links to recipes at the end of the post.

Most visitors to the Akron Art Museum experience Claes Oldenburg’s work. He, with his wife Coosje van Bruggen, were the creators of Inverted Q, the large painted concrete sculpture occupying an honored position at the front door. While the keen observer might pick out the shape of the letter Q on first glance, this large form feels abstract, unlike much of Oldenburg’s oeuvre. His works often transformed everyday objects, playing with scale and texture.

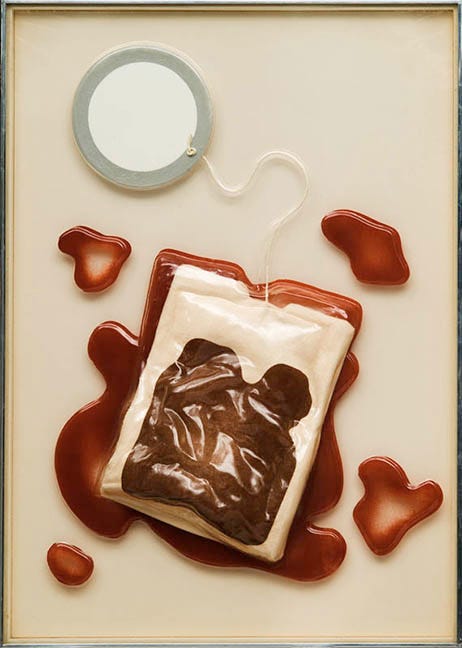

In Tea Bag from 1967, Oldenburg a ubiquitous everyday item into a relief sculpture. Oldenburg notes often in interviews that his work was about transforming items, unlike Dada-artist Marcel Duchamp, for example, “I wasn’t copying; I was remaking them as my own.” This tea bag is increased in size five-fold, with the overall composition being 39 inches high. The greater transformation might be material. A dripping tea bag on a table, something liquid and easily wiped up, becomes vinyl, screenprint on plexiglass, with felt and rayon cord.

What does a work like this mean? Oldenburg is careful to warn viewers to avoid easy interpretation of his works, “This isn’t to say the work is inflected with nostalgia; rather, it reflects the fact that the object only serves as a starting point.” Oldenburg makes the object part of the gallery space in an unexpected manner. With the change in scale and media, the tea bag becomes immaterial, ceding to forms and colors. Yet, are the actual objects not part of the interpretation? Ohio-born artist and sometime Oldenburg collaborator suggested the artist “was looking at American consumer culture and finding New World romance.” Oldenburg was the child of a Swedish diplomat, who while born abroad, was largely raised in Chicago. He acknowledges the Midwestern city was formative in his transformation from immigrant to American.

While raised in the land of deep dish pizza, Oldenberg’s lithograph Flying Pizza shows a large, thin-crusted pie, in the style famous in New York, the city he now resides in. Most people might not imagine bread and tomato taking flight, but Oldenburg’s oeuvre is filled with such fanciful moments. The artist is noted for his skill as a draftsman, but he often notes imagination as his great talent. For him, the artist is meant to explore media and ideas in an effort at “defining what art is.” His imagination was essential in this exploration, but he also wanted these works to be grounded in human life. As he noted, “my art is made for human beings, and it’s important that people enjoy the experience of seeing it.” Everyday objects, like pizza, therefore afford people relevancy and surprise at once. These common objects have an anti-elite quality combined with a host of personal experiences viewers can draw on. Who hasn’t eaten pizza? Yet, who has seen a building-sized pizza fly?

Food, therefore, is a potent tool for Oldenburg. Food has a fluidity and ephemerality that appeals to him. He elucidates, “I like food because you can change it. I mean, there is no such thing as a perfect lamb chop; you can make all types of lamb chops. And that’s true of everything. And people eat it and it changes and disappears.”

Some of Oldenburg’s best known sculptures, like Floor Burger, like the one in the Museum of Modern Art or Dropped Cone, Neumarkt Galerie, Cologne, are commentaries on consumerism, they’re much more about formal concerns. In many ways the content, the meaning of a pizza or a burger don’t matter. As he said, “I always say I’m not doing a hamburger, I’m doing a sculpture.” The plasticity of food, for example, had a great appeal. Food, in its way, is like a sculpture, with its own properties of viscosity, texture, and form. Oldenburg’s efforts at turning food into art brings something common into the viewer’s consciousness.

When Tea Bag was donated to the Akron Art Museum by Case Western Reserve University Art History professor, Harvey Buchanan, he suggested it was “sufficiently ambiguous . . . to be challenging.” Food in Oldenburg’s work embodies many juxtapositions: common and surprising; delicious and inedible; accessible and inscrutable. The overall works are relevant and yet encourage deeper thought. What makes a burger a sandwich and not a sculpture? Why create a fine artwork of a used tea bag? What does it say about our world when we only look at commodities we consume?

The Food:

Oldenburg’s works often show American classics like burgers and pizza. While these are foods most of us usually enjoy at restaurants, in social isolation, you might try your hand at making these old standards at home.

Burger buns are easy to make. The dough can be made without a stand mixer, just make sure to knead well. If you find yourself needing to ration flour and yeast, make just enough buns as people. The recipe is easily halved or doubled.

Oldenburg’s most famous burger is a slim patty with a pickle. But, other sculptures include a fully loaded burger with lettuce, tomato, and mayo. Whatever toppings you have available work great.

Pizza is another Oldenburg-inspired food that’s easy to make. Flying Pizza is a thin-crust pie, made with another simple dough recipe. The key to making a perfect pie is rolling the dough out very carefully so it doesn’t tear. Oldenburg’s pizza solely features cheese, but you can take inspiration from his idea that there is no single ideal for food adding your own toppings.

You might end the meal with ice cream — though don’t feel you need to drop it.

Recipes:

Cooking with the Collection is made possible with support from the Henry V. and Frances W. Christenson Foundation and the Samuel Reese Willis Foundation.

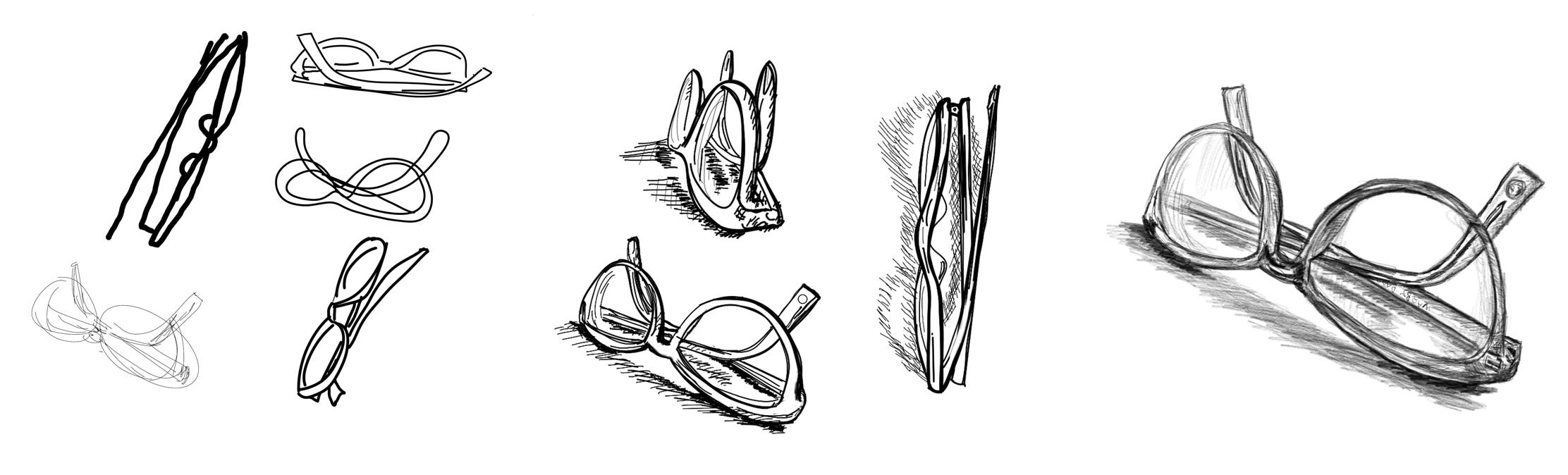

Read MoreDrawing Day

May 16th is an annual celebration of drawing. We’re celebrating by offering you exercises you can try today or any day.

Learning to draw might be on your social isolation to-do list. Or maybe drawing seems too scary to attempt. If you’ve ever written your name on a piece of paper, you’re prepared to learn to draw. (Download our Drawing Day Booklet for more exercises to try.)

Many people think of drawing as the ability to render realistically. But drawing encompasses many forms of expression.

Doodles could be considered a type of drawing. People don’t feel intimidated about doodling. They’re just marks on the side of your notes — not art, you might think. Those same skills, however, can help you feel comfortable drawing. You’ve spent a lifetime doodling, so you are prepared for these lessons.

Holding your Pencil

Writing is an important form of human communication. After you learn to write, you rarely think about the way the pencil or pen is held. Artists, however, often will shift the tool in their hand to get different effects.

- Start by picking up your writing utensil. Write a line.

- Reposition your pencil or pen to hold it an angle. Draw more lines.

- Continue to play with the angle of the writing tool. Explore the different effects on the paper.

Shading

Much of the draftsman’s work is knowing how to use your writing utensil to deliver a variety of lines and shades. Pencil control is learned. Artists spend hours honing their abilities. Try these exercises:

- Filling a sheet of paper with many different strokes.

- Make 7 equal boxes on your paper. Use a pencil to create a graded scale of shades.

- Draw the same item, like a coffee cup, in each of the shades from your scale.

- Draw a houseplant only depicting the shadows.

- Make a drawing using no lines.

Contour

Drawing requires translating the three-dimensional world onto the flat surface. Forms can be rendered using shadows and shading or by focusing on the contour edges. In contour drawing, you focus on the outlines of a form rather than the details.

- Look in the mirror. Draw yourself without looking at the paper. Focus your eyes on your face.

- Draw something in your kitchen. Use a single line.

- Draw your pet using a single line. Draw 7 more contour drawings of your pet as they move. (If you don’t have a pet, draw pets from online videos).

Copying

Drawing requires confidence in your mark-making. Many people falter when they are first trying because their initial sketches don’t “look like anything.” Many artists spend time copying, just as many musicians learn music by playing works written by others. Have you ever tried a step-by-step drawing, like copying a cartoon? Seeing the steps helps you gain confidence. The hardest part of drawing from the real world is translating the three-dimension to a flat surface. When you copy, you translate from one flat surface to another, simplifying the process and increasing your chance of success.

- Try drawing some of the doodles in the gif.

- Try drawing from a magazine.

- Explore the museum’s collection online. Choose 1 work you love. Draw it 20 times.

Vantage Points

Translating three-dimensional space requires learning how to trick the eye. Draftspeople learn how to use line and shadow to imply depth.

- Draw the same object from many different angles.

- Sit on the floor. Draw the room. Find a high stool. Draw the same room.

- Draw your desk and all of its items. Move across the room. Draw your desk again.

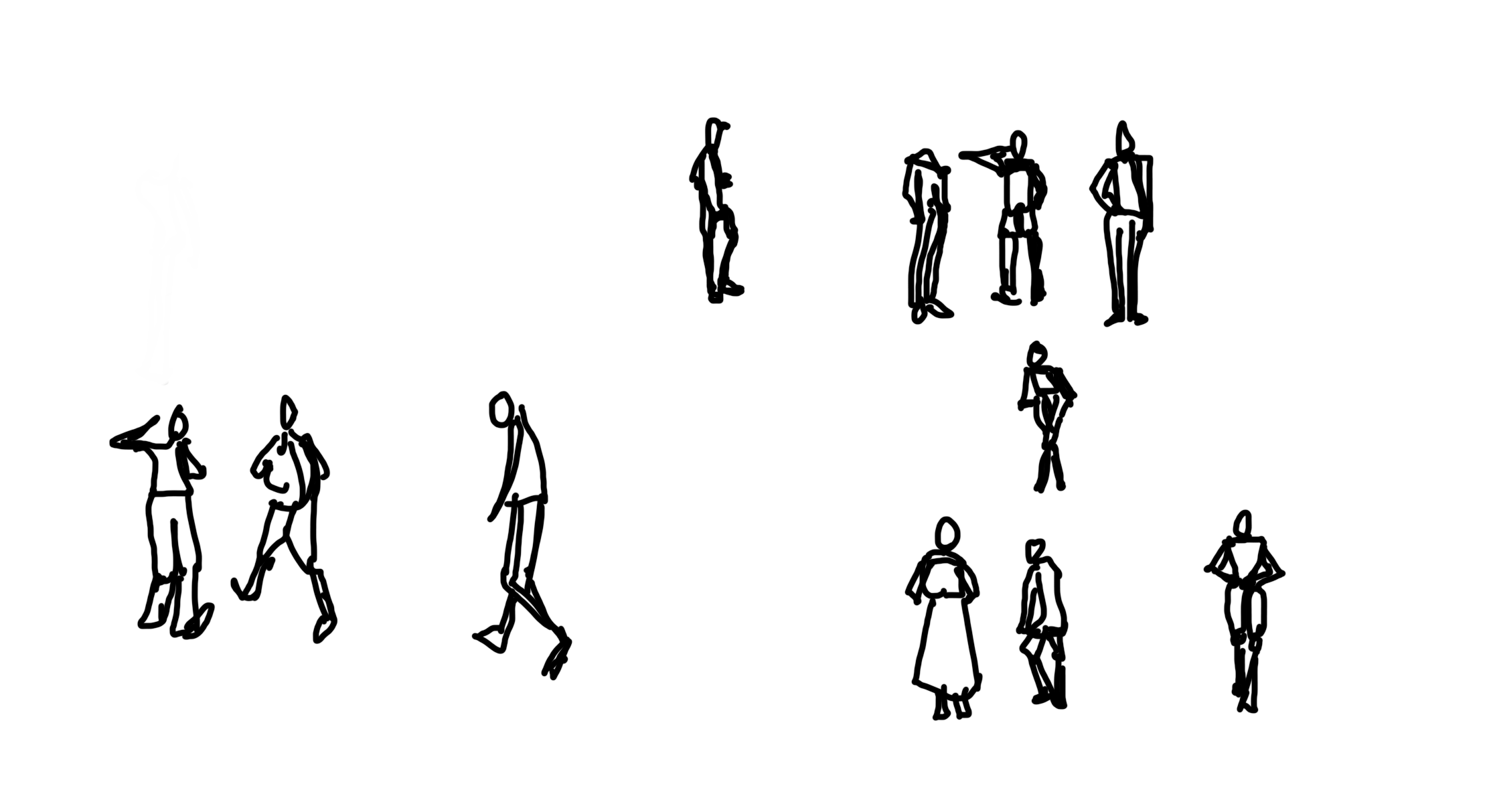

Gesture Drawing

Strong draftspeople not only have confidence and skill but also decisiveness. Hesitancy is visible in halting lines and inconsistent forms.

- Draw the clouds. Start your first drawing on the hour. Make a drawing every hour for a whole day.

- Draw all the people you see in the next show you watch.

- Draw your pet 100 times.

Color

Life is in living color. Adding color to your drawings immediately transforms the level of realism.

- Draw a coffee cup in blue. Draw the same object again in another color. Repeat five more times.

- Draw the forms in your room using 1 color other than black. Add a second color other than black for the shadows.

- Use color to create a drawing using only dots.

- Try any of the exercises in the other sections using color.

Thank you for joining us in this exploration of drawing. This is just the tip of the pencil. Keep drawing and healthy.

Drawing Day — May 16

May 16th is an annual celebration of drawing. We’re celebrating by offering you exercises you can try today or any day.

Learning to draw might be on your social isolation to-do list. Or maybe drawing seems too scary to attempt. If you’ve ever written your name on a piece of paper, you’re prepared to learn to draw. (Download our Drawing Day Booklet for more exercises to try.)

Many people think of drawing as the ability to render realistically. But drawing encompasses many forms of expression.

Drawing though, is a form of communication, a chance to break the rules, a moment to zone out, a safe place to fail, a new place to succeed, and something anyone can do.

Join us here on May 16th for drawing lessons and a downloadable packet filled with exercises. Also check out the other museums celebrating Drawing Day: Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Clyfford Still Museum, Bakersfield Museum of Art, and Catskill Center.

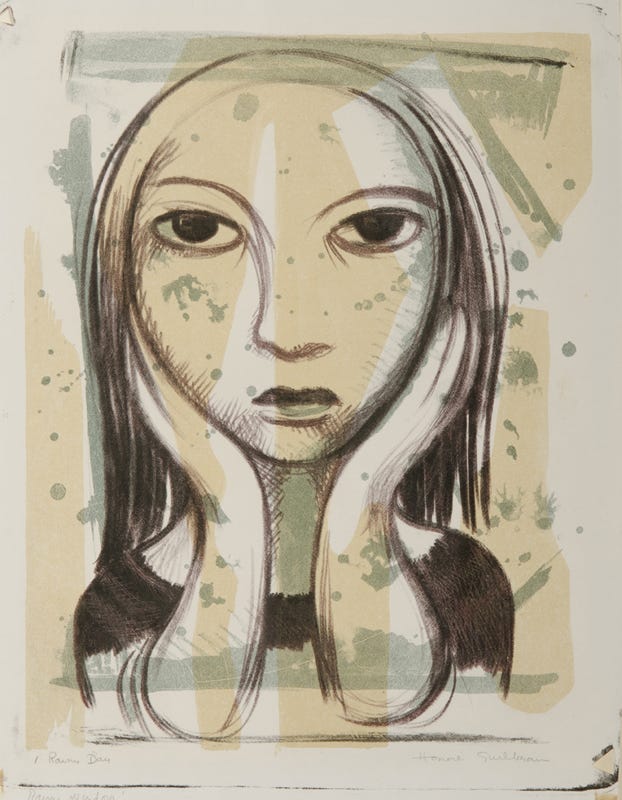

Social Isolation Haircuts

With social distancing, we can’t get to our stylists and barbers. This tour of the collection offers some suggestions for haircuts. You’ll have to decide for yourself if you want to try these styles or not. Take scissors to your coiffe at your own risk.

A blunt bob, slicked back, so people don’t notice you can’t cut straight, like in Honoré Guilbeau’s lithograph. In this print, the woman’s dismay is apparent; perhaps as the title suggests, the rainy day foiled her plans. The artist, northeast Ohio native Honoré Guilbeau, was a dancer and costume designer early in her career before working as part of the Work Project Administration. She went on to teach at the Akron Art Institute in the 1940s before becoming a nationally recognized book illustrator.

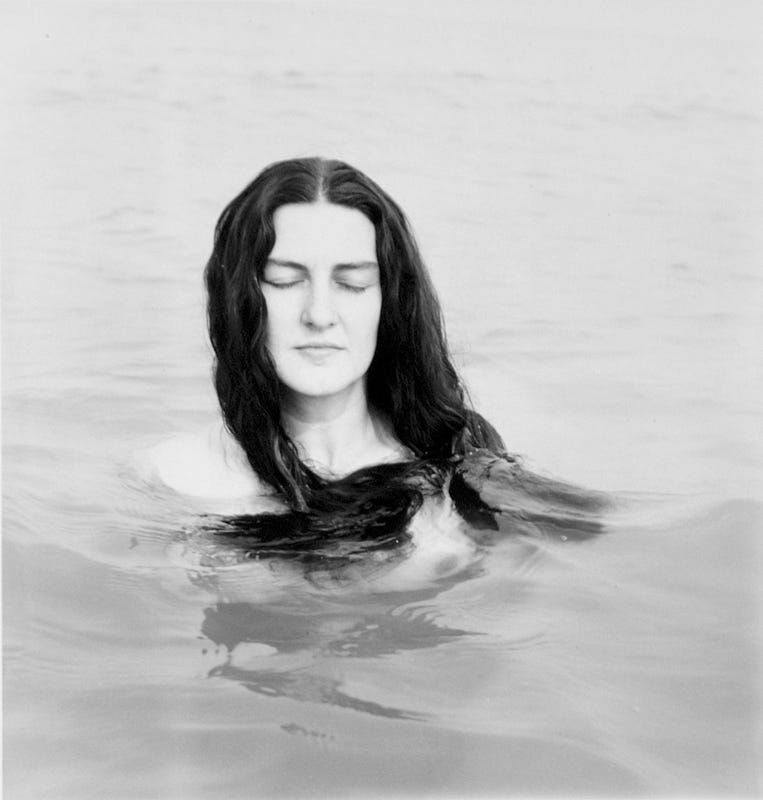

Long, luscious, and wild might be the easiest solution, as in Eleanor Callahan’s locks. Photographer Harry Callahan developed a body of images of his beloved wife, Eleanor. The images were at once fine art and an intimate portrait of a marriage.

With more time on your hands, this might be the chance to try a vintage style, like setting in waves, particularly if you have a willing partner at home to help you get it just right. You don’t even need a special event, like the Spanish wedding this bridesmaid would be attending, to take time to make the extra effort. This particular photograph from 1955 was created by Inge Morath, studio assistant to renowned photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson.

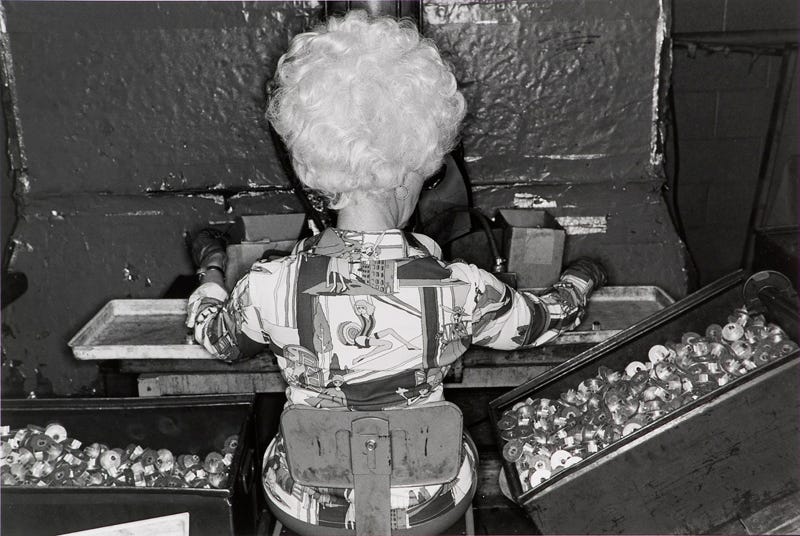

Or, you could go all out and set your hair in a full bouffant. This photograph by Lee Friedlander shows a worker in North Canton toiling in the Hoover factory. Her commitment to style is enviable. The museum’s collection also includes many more photographs by American artist Lee Friedlander taking in the Northeast Ohio region.

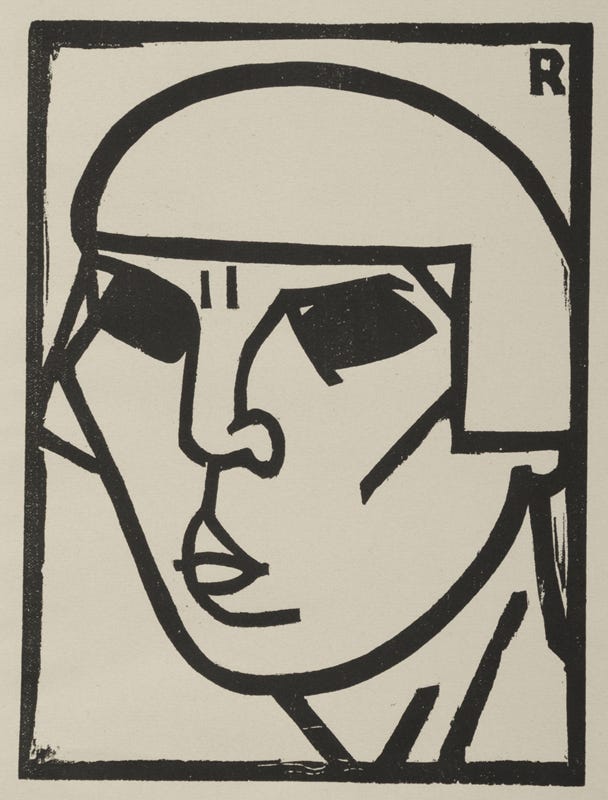

Another option is to get out scissors and snip, snip, snip. You could find yourself with a fashionable, stylish coiffure, particularly given you might have time to get out your straight iron. This woodblock is 100 years old, but the look could work today.

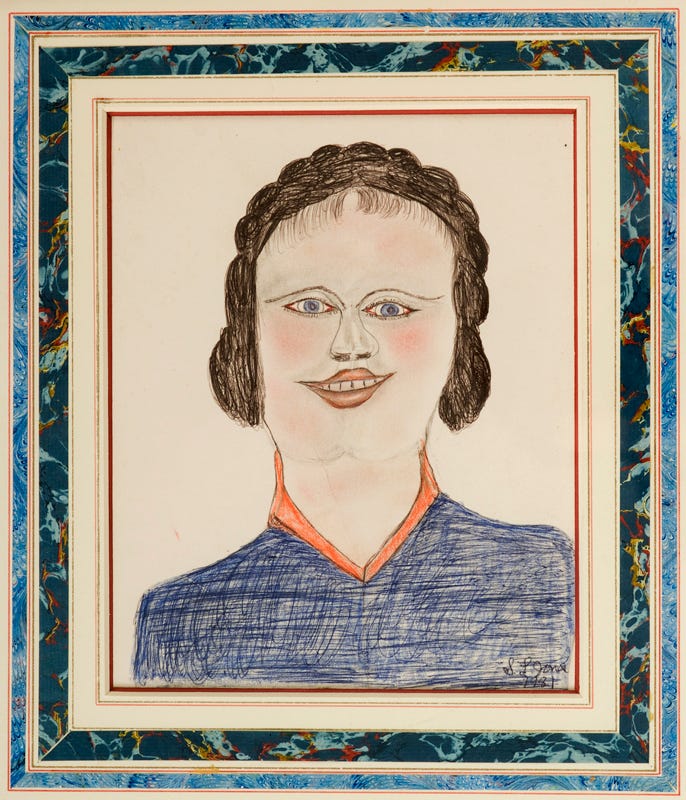

But, be warned, cutting bangs can go awry. This untitled drawing offers you a useful cautionary tale for when you get a little too excited about cutting your bangs.

Then, there is always the easiest option. Just wear a hat, like the lady in Vivian Maier’s photograph. Maier was a prolific photographer with more than 100,000 negatives produced in her five-decade career, creating scenes of life and people in and around Chicago.

Virtual Tours are made possible with support from the Sandra L. and Dennis B. Haslinger Family Foundation, The Sisler McFawn Foundation, The Welty Family Foundation, Dana Pulk Dickinson, and the Lloyd L. & Louise K. Smith Memorial Foundation

Read More